A 'conservation conundrum'—when rat control to conserve one species threatens another

10 May 2024

by Victoria Florence Sperring and Rohan Clarke, The Conversation

Emu - Austral Ornithology (2024). DOI: 10.1080/01584197.2024.2335397">

When pest rats and mice decimate populations of native species, pest control is a no-brainer. But what if baiting rats protects threatened songbirds, while poisoning critically endangered owls?

This is a question conservation managers are grappling with on tiny Norfolk Island, some 1,300 kilometers off the east coast of Australia. They're not the only ones troubled by such conflicting priorities.

Rodents are implicated in the decline of at least 400 threatened species and 30% of bird, mammal and reptile extinctions worldwide. Unfortunately, the most effective rat baits can also kill birds of prey.

Our new research shows the critically endangered Norfolk Island morepork is eating even more rats and mice than previously thought. These birds of prey are being poisoned in the process. We clearly need a way to control or eradicate rodents without killing our native species.

The conservation conundrum on Norfolk Island

As its name suggests, the Norfolk Island morepork is found only on Norfolk Island. Just 25 birds are left in the world, with none held in captivity. The rate of successful breeding is extremely low.

In our new research, we examined the morepork's diet in unprecedented detail.

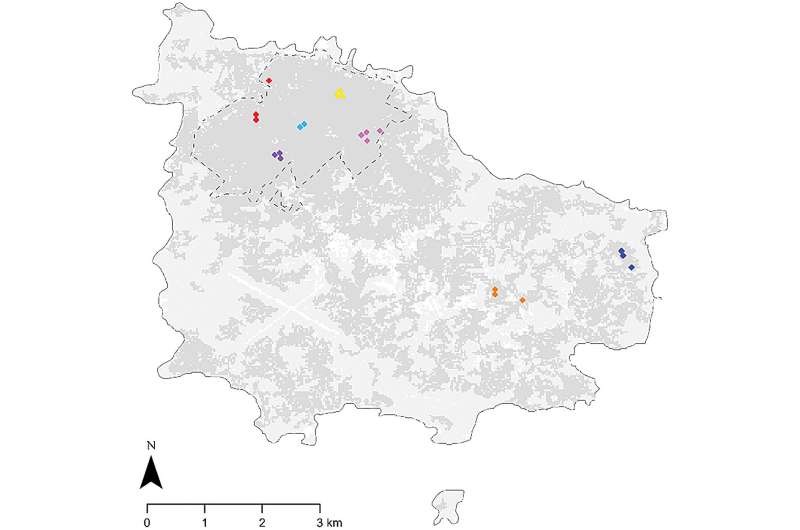

We tracked seven owls, almost a third of the population, to collect their poo and pellets (coughed up like cats do with furballs) for analysis. First we studied the contents by sight, then we sent the samples off for DNA sequencing, to work out what they had been eating.

Every owl in our study had eaten rodents. Two owls had eaten house mice.

When a bird of prey such as a morepork or boobook eats a poisoned rodent, it can become very unwell or die. This is known as secondary poisoning.

During the course of our research, one sick morepork was found and rehabilitated. We named the owl Rashootin after Grigori Rasputin, the Russian mystic who was famously poisoned yet survived. But if Rashootin hadn't been found by an islander, he would not have been so lucky.

Unfortunately we don't know how many other moreporks suffer from secondary poisoning but there is anecdotal evidence it's a problem. The Norfolk Island morepork chicks that hatched between 2011 and 2019 died from a case of suspected secondary poisoning. Elsewhere the incidence of secondary poisoning for boobooks, moreporks and larger Ninox species that eat rodents is well documented.

An obvious solution would be to modify the use of rodent baits on Norfolk island. Perhaps baiting could be less frequent. Or less toxic baits could be used, to reduce the risk of killing non-target species.

But less toxic baits are not so good at killing rats.

Rat control is deemed necessary on Norfolk Island because the rats prey on other threatened species. In our previous research we found rats were https://www.tandfonline.com/do..." target="_blank">the main cause of "nest failure